1960 - 2016

Satellite and UAV Reconnaissance in the Gulf Wars

Satellite and UAV Reconnaissance through the Gulf Wars

Development of modern Satellite imagery and UAV's

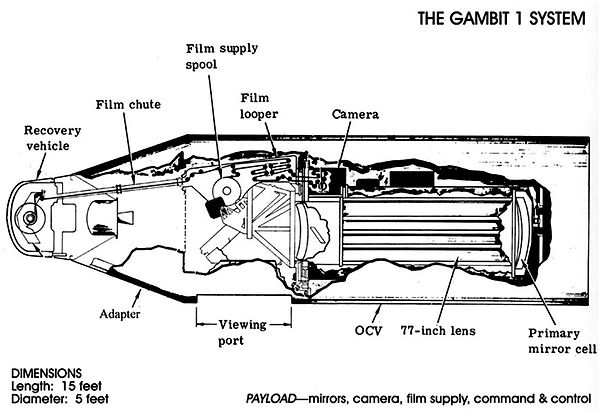

Satellite programs based off of the GAMBIT-1, offered high-resolution imagery, while Vietnam-era UAVs like Ryan 147 enabled persistent surveillance, evolving into the integrations during the Gulf Wars for broad monitoring and real-time data. Systems like Predator used real-time data for precision targeting, reducing manned risks in Scud hunts and counterinsurgency. These modern systems enhanced planning, minimized risk, and safeguarded forces through remote operations.

From 1960 to 2016, satellite and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) systems revolutionized reconnaissance, evolving through large scale conflicts like Vietnam and the Gulf Wars, often referred to as the Desert Wars, to deliver strategic and tactical intelligence. Early satellite programs, such as GAMBIT-1 which launched in 1963, provided high-resolution, detailed imagery of key targets, achieving ground resolutions as fine as one meter during missions from 1963 to 1967. These film-return systems, capturing details of enemy fortifications and troop movements, laid the foundation for enhanced intelligence in the coming wars. In Vietnam, UAVs like the Ryan 147 series conducted high-altitude flights for photographic imagery, reducing risks to manned aircraft while offering around the clock surveillance over hostile areas, such as the Ho Chi Minh Trail. This dual evolution converged during the Gulf Wars, where satellites enabled broad-area monitoring and UAVs provided localized, real-time feeds, fundamentally improving live decision-making and minimizing operational risks.

1

Credit: National Museum of the United States Air Force. "Ryan AQM-34N in the Cold War Gallery at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force."

9

By the 1980s and 1990s, technological advancements allowed for the integration of satellites and UAVs for modular operations. The GAMBIT series satellite, after heavy evolution and multiple iterations, supported precision targeting in Operation Desert Storm by delivering high-resolution, detailed photographic data. UAVs like Pioneer, deployed from ships, offered real-time video for fire direction and battle damage assessment, as well the system helped to enhance artillery fire accuracy while avoiding manned exposure to threats. In the 1991 Gulf War, satellite imagery informed coalition planning, identified layered Iraqi defenses and enabled rapid tactical adjustments. UAVs assisted with real time missile strikes, reducing risks in such vast deserts. Programs such as Aquila, although challenged at first due to budgetary constraints, refined data communication for seamless integration, allowing different branches of the armed forces to adapt strategies dynamically and drastically cut personnel vulnerabilities.

2

8b

Credit: Air Combat Command. "A Predator from the 46th Expeditionary Reconnaissance Squadron landing."

In subsequent operations, including the 2003 Iraq War, systems like Global Hawk and Predator combined satellite images with UAV capabilities. Satellites provided persistent, real-time, and wide-area coverage for troop movements, while Predators processed visuals at medium altitudes, which varied from 3,000 to 25,000 feet, verifying targets and tracking insurgent forces in real-time. During the hunt for Scud missiles in western Iraq, satellite-derived intelligence helped to guide SOF (Special Operation Forces) teams on missions, preventing enemy missile launches and helped to hold down Iraqi forces without large-scale engagements. UAVs, evolving from Vietnam-era models, blended reconnaissance with precision strikes, engaging threats swiftly and effectively. In Iraq and Afghanistan, this united system informed planning, minimized uncertainties such as incorrect targeting, and lowered risks through remote operations, as seen in counterinsurgency efforts where UAVs brought brigade-level awareness to the battlefield from above.

3

Credit: Air Combat Command. "Airman 1st Class Chris Korenaga checks the camera system of an RQ-1 Predator unmanned aerial vehicle."

8a

Smaller UAVs, such as the Raven and Dragon Eye systems, have extended these remarkable capabilities to tactical ground units, enabling hand-held and hand-launched surveillance in urban combat environments for immediate enemy positioning data. Satellites such as the GAMBIT's successors offered high-resolution intel for broader conflict analysis, reducing ground patrol needs. Challenges like bandwidth availability and information relay limits were addressed via sensor fusion and the integration of automatized systems, integrating manned-unmanned teams for rapid, forceful responses. In the Gulf Wars, these technologies shifted counter-insurgency warfare from reactive to proactive, providing critical intelligence that improved real-time decisions and significantly reduced risks, as evidenced by the countless operations minimizing exposure in these dynamic environments.

4

Credit: Smithsonian. "AeroVironment RQ-14A Dragon Eye"

6

Overall, satellite and UAV reconnaissance marked a paradigm shift in warfare, placing an emphasis on adaptability and joint force operations. Early satellites focused on high-resolution imagery, while UAVs added real-time persistence, helping doctrines and strategies evolve for superior battlefield understanding. Experiences from Vietnam through the Gulf Wars highlighted their role in enhancing strategies, delivering vital and timely intelligence, enabling swift decision making, and safeguarding personnel against constantly evolving threats.

5

Credit: Nation Museum of the United States Air Force. "GAMBIT 1 KH-7 Reconnaissance Satellite"

7

Footnotes:

-

Blom, John David. “Unmanned Aerial Systems: A Historical Perspective.” Occasional Paper 37. Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, US Army Combined Armed Center, September 2010. (55-65) ;National Air and Space Museum. “60th Anniversary of the First GAMBIT-1 Photoreconnaissance Satellite Flight.” Jul, 12. 2023. https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/60th-anniversary-first-gambit-1 ;Office of the Secretary of Defense. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Roadmap. Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2001. ;Hastings, Max. Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy, 1945-75. New York: Harper Perennial, 2019.

-

Blom, John David. “Unmanned Aerial Systems: A Historical Perspective.” Occasional Paper 37. Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, US Army Combined Armed Center, September 2010. (66-86) ;National Air and Space Museum. “60th Anniversary of the First GAMBIT-1 Photoreconnaissance Satellite Flight.” Jul, 12. 2023. https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/60th-anniversary-first-gambit-1

-

Call, Steven. Danger Close: Tactical Air Controllers in Afghanistan and Iraq. 1st ed. Military history series, no. 113. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2007. (115-130) ;Filkins, Dexter. The Forever War. New York: Vintage Books, 2008. ;Blom, John David. “Unmanned Aerial Systems: A Historical Perspective.” Occasional Paper 37. Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, US Army Combined Armed Center, September 2010. (86-94)

-

National Air and Space Museum. “60th Anniversary of the First GAMBIT-1 Photoreconnaissance Satellite Flight.” Jul, 12. 2023. https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/60th-anniversary-first-gambit-1 ;Call, Steven. Danger Close: Tactical Air Controllers in Afghanistan and Iraq. 1st ed. Military history series, no. 113. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2007.(124-130) ;Blom, John David. “Unmanned Aerial Systems: A Historical Perspective.” Occasional Paper 37. Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, US Army Combined Armed Center, September 2010. (96-108)

-

Blom, John David. “Unmanned Aerial Systems: A Historical Perspective.” Occasional Paper 37. Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press, US Army Combined Armed Center, September 2010. (68-125) ;Office of the Secretary of Defense. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Roadmap. Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2001.

-

Long, Eric. "AeroVironment RQ-14A Dragon Eye on Display." 2008. Photograph. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Washington, DC (inventory no. A20070211000). (accessed July, 2025).

-

AFB, Wright-Patterson. "GAMBIT 1 KH-7 Reconnaissance Satellite." n.d. Photograph. National Museum of the United States Air Force. (accessed July, 2025).

-

Barclay, Senior Airman Nadine Y. "MQ-1 Predator Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Taking Off from Creech Air Force Base, Nevada." July 15, 2008. Photograph. Air Force, Air Combat Command. (accessed July, 2025).

-

National Museum of the United States Air Force. "Ryan AQM-34N in the Cold War Gallery." n.d. Photograph. National Museum of the United States Air Force, Dayton, OH. (accessed July, 2025).

-

Background: United States Defense Mapping Agency. Hydrographic/Topographic Center. Operation Desert Storm briefing graphic. [Washington, D.C.: The Center, 1991] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/91682184/.(accessed July, 2025).